Knitted into the plot of the novel manuscript I’m working on (which I won’t summarize here) is an estuary restoration project. I’ve drawn on a couple of preserves I’ve visited in recent years to think about what the imagined place might look like, what it is trying to accomplish. Recently, I hiked through the South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve for the first time. The interpretive center (which my hiking guide assured me had fine exhibits) was still closed, as it had been since March of 2020, but the trails were open. We passed a number of other hikers, though the trails were in no way crowded—except with overhanging trees, in places to the point of darkness. Unreal greens, big stumps, orangey afternoon light, remnants of past construction. We walked a balance beam of overgrown clay dike, breached at the end for the tide to re-enter prior pasture. Eroded pilings, mud, bumblebees, a rusting harrow just beyond camera range, boardwalks, monstrous skunk cabbage leaves. The clatter of a kingfisher—a sound whose identification makes me absurdly pleased with myself.

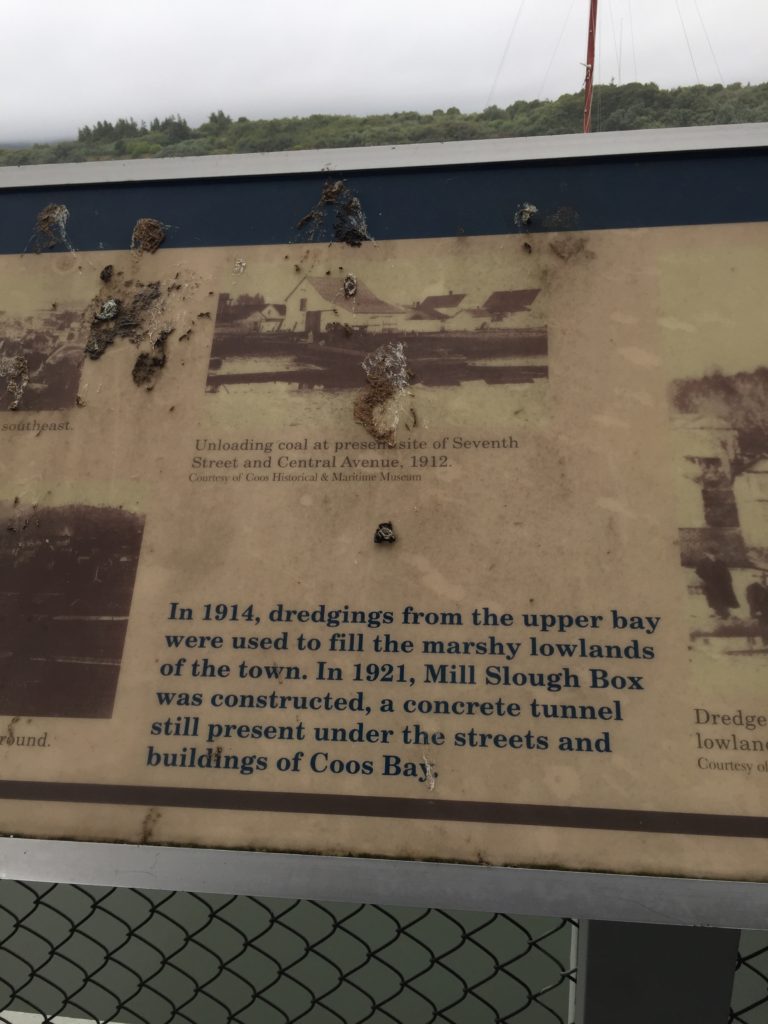

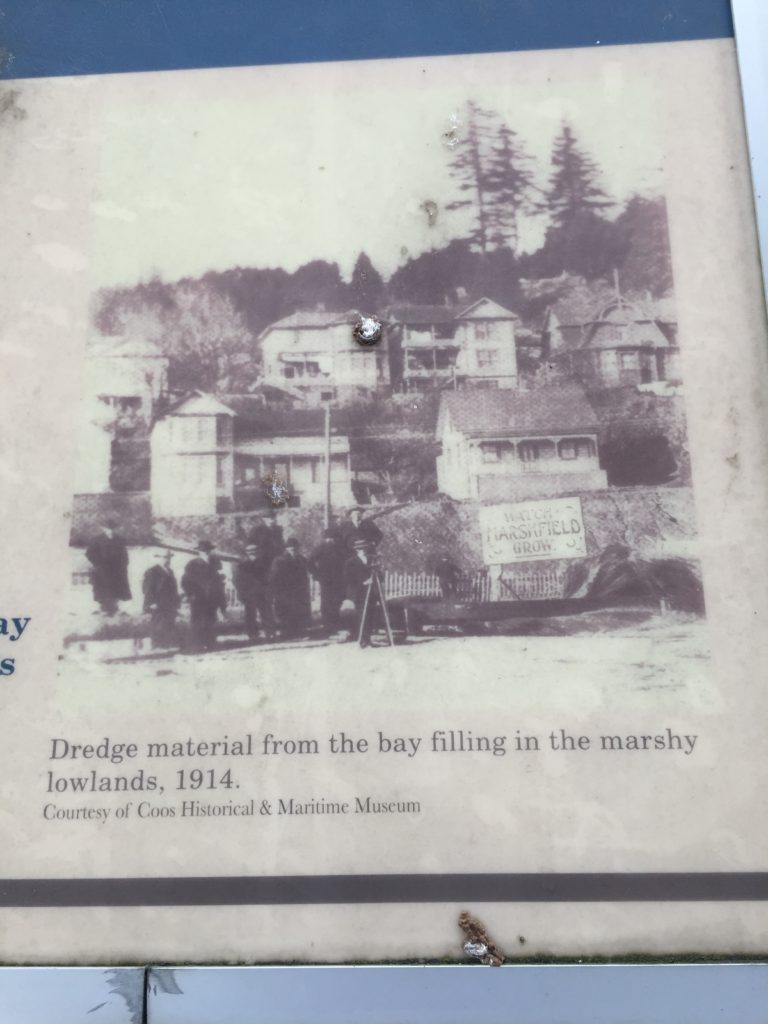

The South Slough Reserve was established in 1974. Restoration is a long process. Success is hard to measure, and conditions change–the climate today is not what it was 45 years ago. In Coos Bay, we read about the local history of dredging and fill on photo placards in an outdoor pavilion itself showing signs of age.

I don’t know yet if the walk will change the story I’m writing, whether the expanded imagery in the back of my mind will make it onto the page. It might not matter. I have a (slightly) better sense than I did of what an estuary is, and why anyone should care, new examples of damage and repair. I explored a place I hadn’t seen before.

Learning more about estuaries, about ecological restoration, has been one way to ground myself in this summer of drought and fire (and, far from where I live, flooding and rain). Writing fiction can be a step away from the fears and tangles of the present, material world; research, in turn, is a step away from the frustrations of plotting or motivating or adequately describing what isn’t yet there. The one reinforces and returns to the other.

One book that has helped me think about water and waterways—on the other side of the continent—is Patricia Hanlon’s Swimming to the Top of the Tide: Finding Life Where Land and Water Meet (Bellevue Literary Press, 2021). Patricia Hanlon‘s website includes swim photos, which I’ve only just now looked at, but the prose is vivid enough on its own. I appreciate the book’s mix of narrative and information, of experience and history, technology and art. I love the image of the author and her spouse slipping, wet-suited, into the tidal creek near dusk, ducking the curious or critical gaze of tourists and busybodies. I like the swimmer’s-eye view when she writes: “At nose level in a saltwater creek, your cupped hands cutting through water the way the snout of a plane cuts through the atmosphere, the horizon is usually only a few feet away. The vanishing point is a canyonlike wall of very firm mud and a dense bamboo forest of grass. Because of the way these tidal creeks twist and turn, there is always something up ahead you can’t see: a cormorant or an egret taking off, fingerling fish darting into shade just as you round the corner” (p. 198). I haven’t done that kind of salt creek swimming, but Hanlon’s story makes me want to.

For the time being, I expect my practice will remain more walking than swimming.